McPhar Co. v.

Sharpe Instruments

citation(s): (1960), 21 Fox Pat. C. 1

|

McPhar Co. v.

|

copyright 1997 Donald M. Cameron, Aird & Berlis

The claims called for the coil to be suspended for free rotation.

The defendant mounted it on top of a tripod, allowing free rotation.

The patent specification contains 71 paragraphs of disclosures and 11 figures and ends with 12 claims of which only Claims 8, 11 and 12 are in suit. These read as follows:

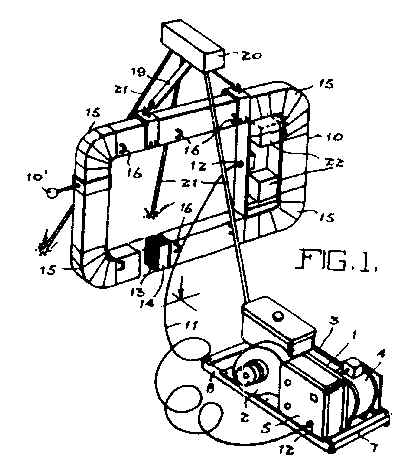

8. A transmitting unit for an electromagnetic clinometer apparatus comprising a motor-driven alternating current generator, a tuned air core transmitting coil of a size to be carried on the back connectable with said generator to form a resonant load for said generator acting to effect frequency regulation thereof, and means to suspend said transmitting coil to hang freely in a vertical plane but orientable in azimuth.

11. A method of prospecting for conducting materials consisting in creating a low frequency alternating magnetic field by means of a transmitting coil suspended to hang vertically and orientable in azimuth and detecting any spacial angle of change of the magnetic field due to the disturbing influence of a conductor material by swinging a search coil located generally in line with the plane of the transmitting coil on an extended axis, and noting the angular position of the axis of said search coil relative the perpendicular for minimum search coil signal.

12. A method as claimed in claim 11 in which said transmitting coil is energized to provide an audio-frequency magnetic field.

"On further consideration I am of the opinion that this statement [that a patent is prima facie valid] is not as wide as the terms of the Act warrant. It must follow from the provisions of the Act that a patent granted under it shall thereafter be prima facie valid and avail its grantee and his legal representatives for the term of the patent, that the onus of showing that it is invalid lies on the person attacking it, no matter what the ground of attack may be, and that until it has been shown to be invalid the statutory presumption of its validity remains.

This does not mean that the patent is immune from attack or that the patentee is free from the obligations that are incumbent on him by way of consideration for the grant of the patent monopoly to him but it seems clear that, since Parliament has deliberately endowed a patent granted under the Act with the presumption of validity, the onus of showing that such a patent is invalid is not an easy one to discharge. That being so, the English decisions indicating that a patentee must prove the existence of the essential attributes of the patentability of the invention covered by its patent before he can succeed in an action for damages for infringement of his rights under his patent are no longer applicable in Canada.

He need not prove the existence of these attributes for he starts with a statutory presumption of their existence in his favour and the onus of showing their non-existence lies on the alleged infringer of the patent. The enactment of the statutory presumption of validity effected an important change in Canadian patent law and marked a substantial advance in the protection of a patentee's rights."

At pp. 55-59

"It has long been established that if a person takes the substance of an invention he is guilty of infringement even if his act does not in every respect fall within the express terms of the claim defining it. This basic principle was stated as early as 1875 by James L.J. in Clark v. Adie (1875), 10 Ch. Ap. 667 at 675 in the following terms:

"A patent for a new combination or arrangement is to be entitled to the same protection, and on the same principles, as every other patent. In fact, every, or almost every, patent is a patent for a new combination. The patent is for the entire combination, but there is, or may be, an essence or substance of the invention underlying the mere accident of form; and that invention, like very other invention, may be pirated by a theft in a disguised or mutilated form, and it will be in every case a question of fact whether the alleged piracy is the same in substance and effect, or is a substantially new or different combination."

When Clark v. Adie went to the House of Lords (1876-7), 2 App. Cas 315, the Lord Chancellor (Lord Cairns) discussed the various ways in which a patent for an apparatus could be infringed. In the course of his discussion he said, at page 320:

"The infringer might not take the whole of the instrument here described, but he might take a certain number of parts of the instrument described; he might take an instrument which in many respects would resemble the patent instrument, but would not resemble it in all its parts. And there the question would be, ..., whether that which was done by the alleged infringer amounted to a colourable departure from the instrument patented, and whether in what he had done he had not really taken and adopted the substance of the instrument patented. And it might well be, that if the instrument patented consisted of twelve different steps,..., an infringer who took eight or nine or ten of those steps might be held by the tribunal judging of the patent to have taken in substance the pith and marrow of the invention, although there were one, two, three, four or five steps which he might not actually have taken and represented upon his machine."

Lord Cairns appears to have been the originator of the mixed metaphor "the pith and marrow of the invention". While the metaphor has been criticized the principle enunciated in Clark v. Adie (supra) has been followed and applied in many cases, both in Great Britain and in Canada, and has never been repudiated: vide, for example, Procter v. Bennis et al. (1887), 4 R.P.C. 333 at 345, 352, 362; Benno Jaffe und Darmstaedter Lanolin Fabrik v. John Richardson and Co. (Leicester) Ltd. (1894), 11 R.P.C. 93 at 112, 261; The Incandescent Gas Light Company, Ltd. v. The De Mare Incandescent Gas Light System, Ld., et al. (1896), 13 R.P.C. 301 at 331, 559 at 571, 579; Marconi v. British Radio Telegraph and Telephone Company Ld. (1911), 28 R.P.C. 181 at 217; British Thomson-Houston Co. Ld. v. Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Co. Ld. (1928), 45 R.P.C. 1 at 25; The Rheostatic Company Limited v. Robert McLaren and Company Limited (1936), 53 R.P.C. 109 at 118; Lightning Fastener Co., Ltd. v. Colonial Co., Ltd. et al. [1932] Ex. C.R. 89 at 98, 100, [1934] 51 R.P.C. 349 at 367; Dominion Manufacturers Ltd. v. Electrolier Manufacturing Co. Ltd. [1933] Ex. C.R. 141 at 146, [1934] S.C.R. 436 at 443; Samson-United of Canada et al. v. Canadian Tire Corpn, Ltd. [1939] Ex.C.R. 277; [1940] S.C.R. 386.

In Clark v. Adie (supra) Lord Cairns did not specifically refer to the doctrine of mechanical equivalency but it is implied in his statement. Indeed, it is only a particular application of the general doctrine enunciated by him. That this is so was stated by Romer L.J. in R.C.A. Photophone Ld. v. Gaumont-British Picture Corporation Ltd. and British Acoustic Films, Ld. (1936), 53 R.P.C. 167 at 197, where he said of it:

"The principle is, indeed, no more than a particular application of the more general principle that a person who takes what in the familiar, though oddly mixed metaphor is called the pith and marrow of the invention is an infringer. If he takes the pith and marrow of the invention he commits an infringement even though he omits an unessential part. So, too, he commits an infringement if, instead of omitting an unessential part, he substitutes for that part a mechanical equivalent."

There was recognition of this fact in Marconi v. ,em>British Radio Telegraph and Telephone Company Ld. (1911), 28 R.P.C. 181 at 217. There Parker, J. stated the general principle that Lord Cairns had laid down in these terms:

"It is a well-known rule of Patent law that no one who borrows the substance of a patented invention can escape the consequences of infringement by making immaterial variations. From this point of view, the question is whether the infringing apparatus is substantially the same as the apparatus said to have been infringed"

and then said

"where the Patent is for a combination of parts or a process, and the combination or process, besides being itself new, produces new and useful results; everyone who produces the same results by using the essential parts of the combination or process is an infringer, even though he has, in fact, altered the combination or process by omitting some unessential part or step and substituting another part or step, which is, in fact, equivalent to the part or step he has omitted."

This statement, which is confirmatory of the rule laid down by Cotton L.J. in Procter v. Bennis et al. (1887), 4 R.P.C. 333, is in my opinion, the best statement of the doctrine of equivalency that can be found in the reports. Its application of course is subject to the limitation implied in the statement, which Parker J. put explicitly as follows:

"The question... is a question of the essential features of the invention said to have been infringed. If that part of the combination, or that step in the process for which an equivalent has been substituted, be the essential feature, or one of the essential features, then there is no room for the doctrine of equivalents."

Thus it is established law that if a person takes the substance of an invention he is guilty of infringement and it does not matter whether he omits a feature that is not essential to it or substitutes an equivalent for it. The case of The Incandescent Gas Light Company Ld. v. The De Mare Incandescent Gas Light System, Ld. et al. (supra) is an early illustration of the former and the case of Benno Jaffe und Darmstaedter Lanolin Fabrik v. John Richard and Co. (Leicester), Ltd. (supra) an early illustration of the latter.

In the Incandescent Gas Light Company case (supra) Willis J. held that the defendants had taken the substance of the patentee's invention, notwithstanding the fact that they used a prescription that was somewhat different from that described in the specification and omitted a substance that had been specified in the specification and accordingly included in the patentee's claim. On appeal to the Court of Appeal (1896), 13 R.P.C. 559 his judgment was unanimously affirmed.

And in the Benno Jaffe und Darmstaedter Lanolin Fabrik case (supra) the facts were that the defendants adopted in substance the whole process of the patent, the only difference being that instead of using a centrifugal machine they substituted a settling tank to do what the centrifugal machine was intended to do. Romer J. held that the use of the centrifugal machine was not of the essence of the invention and that since the defendants had taken the essence they had infringed. At page 112, he said:

"They appear to me to have taken the essence, or what is sometimes called the pith and marrow, of the invention. The use of the centrifugal machine was not of the essence of the invention. That machine was a well known method of separating mechanically materials of different specific gravity, and was, to my mind, referred to in the Specification as being and because it was the most speedy and efficient known means for effecting the separation. The mechanical separation, by allowing gravity to act on such materials when deposited in a vessel in the ordinary way is a well known equivalent, though not so speedy or efficacious, and the Defendants cannot by adopting this, when they in all essential matters take and use the Plaintiff's invention, be heard to say that they are not using that invention or infringing the patent."

The Court of Appeal (1894), 11 R.P.C. 261, affirmed the decision of Romer J., holding that the use of the centrifugal machine was not an essential part of the invention, that the defendants had taken every step of the plaintiff's process except the centrifugal machine, that the substitution of a depositing tank for the centrifugal machine was the substitution of a mere manufacturing equivalent and that the defendants had accordingly infringed. I might add that the language of Romer J. is, mutatis mutandis, appropriate to the facts of the present case.

And it is also established law that a plaintiff can resort to the doctrine of equivalency only in respect of a feature of the invention claimed by him that is not essential to it. In every case where it is sought to apply the doctrine a particular issue arises, namely, whether the feature of the invention in respect of which an equivalent is alleged to have been used is essential to the invention."

Return to:

Cameron's IT Law: Home Page; Index

Cameron's Canadian Patent & Trade Secrets Law: Home Page; Index